Ideal positioning can make the difference between a successful endotracheal intubation or death. Many times, intubations are performed in emergency situations, and positioning is not always ideal depending on the type of surface. In the operating room (OR), ideal conditions exist regarding adequate supplies and time.1 Conditions can be very different outside of the OR especially during a code blue. The average time of rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is 37 seconds in the emergency room.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic RSI was being performed as quickly as 15 seconds in the intensive care unit to prevent cardiac arrest in patients with severe ARDS.3

Hospital beds are cumbersome and can cause poor positioning making intubation difficult. If possible, it is always a good idea to have a few towels available to help with head positioning. Towels can be rolled up and placed in between the shoulder blades to aid in simple head extension. Towels can also be used to flex the neck on the chest and extend the head on the neck into the sniffing position. Pillows can be added if needed in morbidly obese patients.

More: Training Tips for CPAP and BiPAP

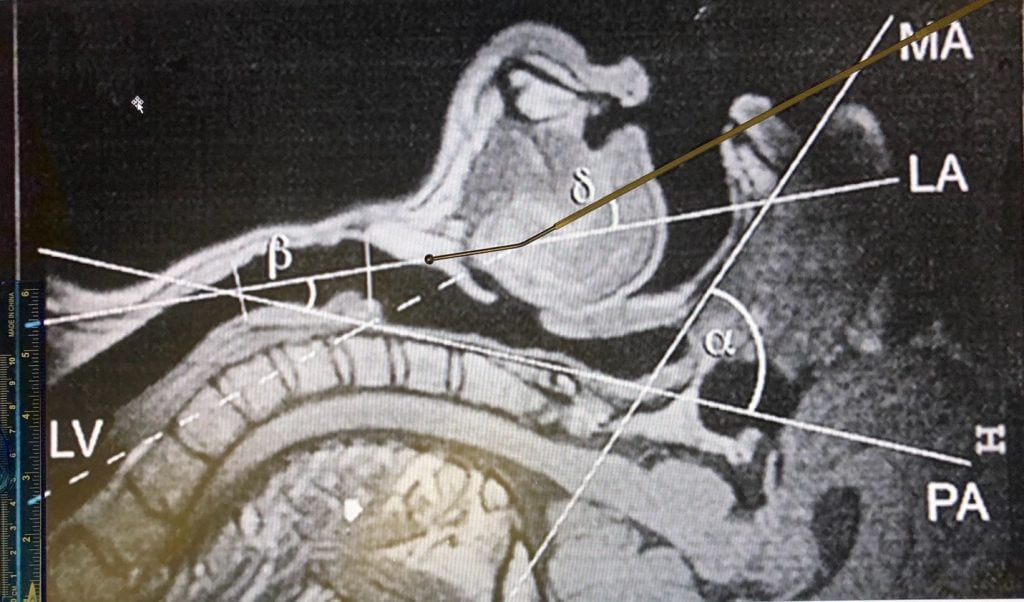

Previous studies published in the Journal of Anesthesia comparing head positioning with regards to laryngeal axis (LA), line of vision (LV), oral axis (OA) and pharyngeal axis (PA) proved that all axes can never be perfectly aligned.4 The same authors concluded that routine use of the sniffing position appears to provide no significant advantage over simple head extension for tracheal intubation using a Macintosh 3 blade.5 The sniffing position improved glottic exposure in 18% of patients and worsened it in 11%, in comparison with simple head extension in patients intubated in the operating room. Multivariant analysis showed that patients with reduced neck mobility and obesity did better in the sniffing position.

Fig. 1. Evolution of the four axes (mouth axis [MA], pharyngeal axis [PA], laryngeal axis [LA], line of vision [LV]) and the α, ß, and ó angles in the three head positions. The magnetic resonance images are shown for patient no. 5. (A) Neutral position; (B) simple head extension; (C) “sniffing” position.4

![Fig. 1. Evolution of the four axes (mouth axis [MA], pharyngeal axis [PA], laryngeal axis [LA], line of vision [LV]) and the α, ß, and ó angles in the three head positions. The magnetic resonance images are shown for patient no. 5. (A) Neutral position; (B) simple head extension; (C) “sniffing” position.4](https://emsairway.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/A.jpg)

The angle between the line of vision (LV) to the laryngeal axis (LA), delta (ó), decreases significantly when placed in simple head extension (B) and the sniffing position (C) compared with neutral positioning (A). In simple head extension the delta angle is the smallest approximating 20-degrees. The smaller the delta, the easier it is to access the glottis.

More: Non-Respiratory Disease Pathologies That May Complicate Airway Management

The single-use telescopic endotracheal intubation bougie, AIROD®, was designed with the perfect 20-degree angle that allows easy transition from the line of vision (LV) to the laryngeal axis (LA) in simple head extension.6-9

Fig. 2. AIROD® aligned perfectly with the line of vision (LV) with the head in simple extension. Transition to the laryngeal axis (LA) is easy due to the specialized 20-degree tip.

In the simple extension position, the AIROD® transitions easily from the line of vision to the laryngeal axis due to its’ 20-degree angled tip facilitating endotracheal intubation. If needed, the AIROD® is able to augment the view of the glottis by lifting the epiglottis to provide the best view of the vocal cords.

When determining the ideal head position to perform endotracheal intubation, one needs to take into consideration the degree of neck mobility and the BMI of the patient. All clinicians should be comfortable with both simple neck extension and the sniffing position so that the best view of the vocal cords can be obtained leading to the safest intubation possible.

References

- Sasano, Nobuko, et al. Time progression from the patient’s operating room entrance to incision: factors affecting anesthetic setup and surgical preparation times. J Anesh. 2009.

- Driver B, Prekkar M, Klein L, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(21):2179-2189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6496.

- Schmitz ED. Decreasing COVID-19 Patient Risk and Improving Operator Safety with the AIROD® During Endotracheal Intubation. J of Emergency Medical Services.

- Frederic A, et al. Study of the “Sniffing Position” by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Anesthesiology 2001;94:83-6.

- Frederic A, et al. Randomized Study Comparing the “Sniffing Position” with Simple Head Extension for Laryngoscopic View in Elective Surgery Patients. Anesthesiology 2001;95:836-41.

- Schmitz ED, Park K. First-Attempt Endotracheal Intubation Success Rate Using A Telescoping Steel Bougie. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;22(1)36-40.

- Schmitz ED, Park K. Emergency Intubation of a Critically Ill Patient with a Difficult Airway and Avoidance of Cricothyrotomy Using the AIROD®. J of Emergency Medical Services.

- Schmitz ED. Single-use telescopic bougie case series. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(2):64-8.

- Schmitz ED. AIROD® Case Series: A New Bougie for Endotracheal and Trauma Care. Vol5.No2:22.

Evan D. Schmitz, MD is a board certified pulmonary and critical care physician and the inventor of the AIROD®.

Recent Comments