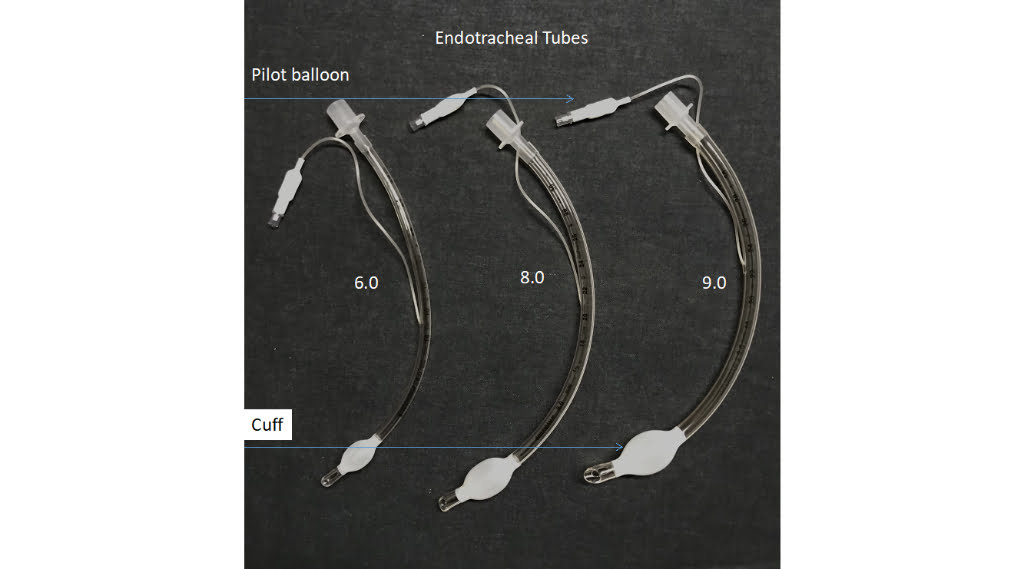

On scene of a car versus tree crash, the mid-20-year-old male driver is not breathing adequately, requiring rapid sequence intubation. After successfully placing an 8.0 mm endotracheal tube, the patient is placed on the ventilator producing bubbling secretions from the mouth. Plunging air from a 10 cc syringe into the pilot balloon extinguishes the problem immediately. The patient is loaded into the rotorcraft for transport to the Level I trauma center one hour away. On lift-off, the bubbling secretions from the mouth reappear, and the ventilator is alarming “low pressure”.

The pilot balloon feels “soft,” so after suctioning the oropharynx, another 10 cc of air is plunged in, followed by another 5 cc, “for good measure.” Now the pilot balloon feels firm, the gurgling and bubbling has stopped, and after an alarm reset, the low-pressure alarm no longer appears. Problem solved; no harm-no foul?

Previous: Respiratory Failure Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Well, maybe. Complications, some serious, can occur from improper pressure when sealing an airway cuff in the trachea. Over-inflation of the cuff can result in tracheal stenosis, tracheal necrosis, tracheomalacia, and fistula formation to the esophagus or innominate artery.1 The ETT cuff pressure associated with impaired tracheal capillary perfusion ranges between 30 and 50 cm H2O (CWP).2 There are risks with under-inflation as well, such as silent aspiration, and ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). Ideally, cuff pressures should be maintained between 20 and 30 CWP.3

A concern when transporting an intubated patient by rotor or fixed wing aircraft is the effect of cabin pressure changes on cuff pressures. Boyles law tells us that the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to the pressure to which it is subjected, when temperature remains constant.4 Therefore, as altitude increases, the volume of trapped air in the cuff will increase, possibly causing injury to the tracheal mucosa. It is common practice to monitor and adjust cuff pressures as altitude changes are made.

Photo courtesy of Vent-Pro Training

There has been considerable research published on monitoring cuff pressures. One study involving Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) produced some astounding findings. Of 55 patients sampled, the mean ET tube cuff pressure was 70 CWP – a full 40 CWP above the maximum accepted level of 30 CWP.5 Again, a cuff pressure between 20 and 30 CWP is recommended to provide an adequate seal and reduce the risk of complications.6

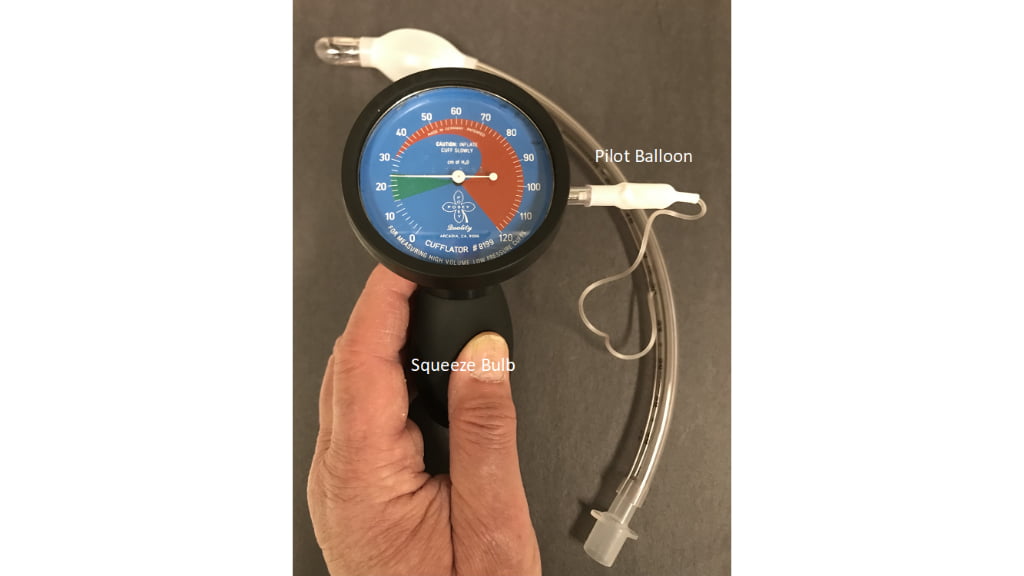

Cuff pressure manometer (AKA Cufflator)

The above photo shows an out-of-range cuff pressure at 80 CWP. (Photo courtesy of Vent-Pro Training)

Above photo shows an acceptable cuff pressure range of 24 CWP. (Photo courtesy of Vent-Pro Training)

The goal is to maintain cuff pressures that prevent aspiration, support delivered tidal volume/pressures and do not interfere with tracheal perfusion. So how is this goal accomplished? In the hospital setting, nurses and respiratory therapists ensure adequate management of ETT cuff pressure, although in the United States, nurses often rely on respiratory therapists to manage the ETT cuff pressures.7 Monitoring and adjusting cuff pressures should be done at minimum every 8-12 hours and PRN. Situations that may contribute to fluctuations in pressure include suctioning, positioning the patient, and coughing.

There are many devices available to measure and monitor cuff pressures. Sometimes called cuff manometers, these devices have a pressure gauge and a manual inflation squeeze bulb. The device attaches to the pilot balloon and directly reads the pressure inside the ET tube cuff. From the reading obtained, air can be added to or removed from the cuff to achieve the acceptable 20-30 CWP range. It is possible to a make simple device using a three-way stop cock, 10 cc syringe, and a pressure gauge, with the necessary tubing to connect to the pilot balloon. There are also electronic devices that can be attached to the cuff pilot to continually monitor and adjust cuff pressures in real time.

Another strategy to measure cuff pressures is called minimal leak technique (MLT) and has been shown to produce safer pressures than a fixed volume (10 cc syringe) strategy. The procedure starts by suctioning the oropharynx and the trachea with the cuff fully inflated. A stethoscope is then placed over the trachea and air is slowly withdrawn from the pilot balloon. When a slight leak is heard at the end of inspiration, the MLT has been achieved. Some clinicians will add 0.2 cc or slightly more to seal the leak. This would be considered the minimal occluding technique (MOT).

There are many variables to consider when discussing cuff pressures. An appropriately sized ET tube for the patient is an important first step. Using a high-volume-low-pressure style balloons can be helpful. Some strategies involve replacing air with water prior to air medical flights to eliminate trapped air expansion at higher altitudes. A foam cuff is sometimes used on trached patients, expanding when open to atmospheric pressure and is gentle on the trachea.

Photo courtesy of Vent-Pro Training

Some “seasoned veterans” like to use the palpation technique where the pilot balloon is squeezed to confirm air is in the cuff. Some clinicians prefer to use a predetermined volume technique where a specific amount of air is injected into the pilot balloon. While these practices assure a seal, it is far more accurate and acceptable to use a direct intracuff pressure monitoring device to obtain a quantitative pressure reading.

The main goal when transporting a mechanically ventilated patient is safety and patient comfort. Research has demonstrated that cuff pressures during transport have frequently been out of range; it is strongly recommended that health care practitioners monitor and adjust cuff pressures accordingly when transporting any mechanically ventilated patient.

References

- Hess, DR, Kacmarek, RM. Essentials of Mechanical Ventilation, 3rd New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2014.

- Benumof JL, Cooper SD. Quantitative improvement in laryngoscopic view by optimal external laryngeal manipulation. J Clin Anesth. 1996; 8:136–140. [PubMed: 8695096]

- Hess, DR, Kacmarek, RM. Essentials of Mechanical Ventilation, 3rd New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2014.

- American College of Emergency Physicians, Pollak, AN, ed. Critical Care Transport,2nd Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

- Tennyson, J, Ford-Webb, T, Weisberg, S, LeBlanc, D. Endotracheal Tube Cuff Pressures in Patients Intubated Prior to Helicopter EMS Transport. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 2016; 17:721-725.

- Diaz E, Rodriguez AH, Rello J. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: issues related to the artificial airway. Respir Care. 2005; 50:900–906. [PubMed: 15972111]

- Sole ML, Byers JF, Ludy JE, Ostrow CL. Suctioning techniques and airway management practices: pilot study and instrument evaluation. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:363–368. [PubMed: 12102437]

Michael Schauf, RRT-NPS, has been a registered respiratory therapist at Albany Medical Center Hospital in New York since 1994. He covers all in-patient units, ICUs, the adult and pediatric Emergency Departments and is a member of the neonatal/pediatric transport team at this Level I Trauma and Level 3 NICU Center. Michael is the founder of Vent-Pro Training, teaching medics and nurses around the world how to manage mechanically ventilated patients during ground, rotor, and fixed-wing transports. He has been a flight respiratory therapist since 1998, currently working for AirMed and as a clinical education specialist for AMR. Michael authored the respiratory chapter of, “Critical Care Transport, 2nd edition,” published by Jones & Bartlett and is an adjunct instructor in the Respiratory Care Program at Hudson Valley Community College.

Recent Comments