Abstract

An estimated 10% of newborns need help to establish lung aeration, which remains the most critical step of neonatal resuscitation; therefore, endotracheal intubation is a mandatory skill for neonatal trainees. However, neonatal intubation is also a difficult skill to learn and teach, primarily due to the lack of an adequate number of on the job opportunities to enable rapid development of proficient skill levels. Reported first-attempt success rates are only between 20% and 73% and those with the least experience have the lowest success rates. Adverse events occur in 39% of intubations and serious adverse events in 9%.

Therefore, strategies to optimize first-attempt success rates are critically needed; multiple attempts cause adverse events. Macintosh laryngoscopy assisted by a single-person bougie technique and the jaw-thrust maneuver, when necessary, is needed to increase first-attempt success rates, particularly when intubation is performed by neonatal trainees. Macintosh laryngoscopy assisted by a single-person bougie technique and the jaw-thrust maneuver, when necessary, is also needed to increase first-attempt success rates when intubation is performed by paramedics and other healthcare professionals who are neither anesthesiologists nor CRNAs.

Previous: A First in Nepal: A Patient Intubated Inside a Fixed-Wing Aircraft

Manuscript

More than fifty percent of pediatric arrests occur in children <1 yr of age and more commonly in males (~60%).1,2 An estimated 10% of newborns need help to establish lung aeration, which remains the most critical step of neonatal resuscitation,3; therefore, endotracheal intubation is a mandatory skill for neonatal trainees. However, neonatal intubation is also a difficult skill to learn and teach, primarily due to the lack of an adequate number of on the job opportunities to enable rapid development of proficient skill levels.4 One study of Macintosh laryngoscopy in adults, shows that the intubation learning curve reached a 90% success rate after a mean of 57 attempts.5 Reported first-attempt success rates of those performing intubation are only between 20% and 73% and those with the least experience have the lowest success rates.6-13 Three studies report that first-attempt success rates by neonatal trainees are less than 25%.6,7,9

In a prospective study, adverse events occurred in 39% of intubations and serious adverse events in 9%.14 Therefore, strategies to optimize first-attempt intubation success rates are critically needed; multiple attempts cause adverse events. Macintosh laryngoscopy assisted by a single-person bougie technique and the jaw-thrust maneuver, when necessary, is needed to increase first-attempt success rates, particularly when intubation is performed by neonatal trainees. Macintosh laryngoscopy assisted by a single-person bougie technique and the jaw-thrust maneuver, when necessary, is also needed to increase first-attempt success rates when intubation is performed by paramedics and other healthcare professionals who are neither anesthesiologists nor CRNAs. While neonatologists get experience intubating 1 of every 10 patients they treat and often have low first-attempt success rates, paramedics have far less on the job experiences to hone their skills. In fact, one study in Pennsylvania showed that paramedics performed a median of only 1 intubation per year (interquartile range, 0-3; range, 0-23). Of 5,245 rescuers, >67% (3,551) performed two or fewer intubations, and >39% (2,054) rescuers did not perform any intubation.

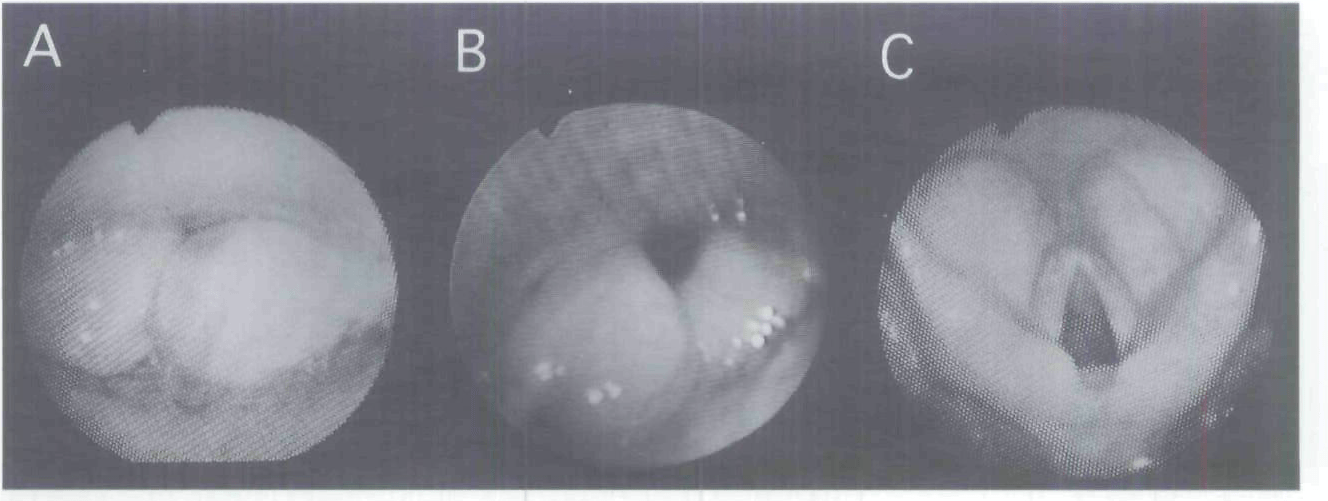

Laryngoscopy is performed to expose the larynx and overcome the collapse of the laryngeal inlet (or glottis) when anesthesia with or without muscle relaxation is used.16,17 Any loss of tone in the laryngeal muscles causes collapse of the glottis; therefore, without the jaw-thrust maneuver, it is completely collapsed in 10% of patients and partially in 90% (see figure 1).17

Figure 1

A: Fully collapsed laryngeal aperture due to use of anesthetic agent with or without muscle relaxation.

B: Partially collapsed laryngeal aperture due to use of anesthetic agent with or without muscle relaxation.

C: Jaw thrust fully expanding a collapsed laryngeal aperture.

Image used with permission from Wiley. Murashima K, Fukutome T. Effect of jaw-thrust manoeuvre on the laryngeal inlet. Anaesthesia 1998;53:203-4.

When jaw-thrust is applied, the inlet is completely expanded (see figure 1). The direction of force applied to the Macintosh laryngoscope must be such that the force is exerted optimally on the hyoepiglottic ligament, which is required to expose the larynx by adequately lifting the epiglottis, and when anesthesia with or without muscle relaxation is used, expand a collapsed laryngeal aperture.16 Even when correctly performed by experienced anesthesiologists, Macintosh laryngoscopy may not exert force adequately on the hyoepiglottic ligament, thereby requiring blind intubation and troubleshooting measures such as jaw-thrust from an assistant, which fully expands a collapsed laryngeal aperture[16]. Laryngoscopy was difficult in only 17 of 587 patients in which all views were a Cormack-Lehane grade 3. Therefore, Cormack-Lehane grade 4 views are extremely rare. Blind intubation with an endotracheal tube (ETT) + stylet was easy in 13 of these patients. However, if the laryngoscope could not adequately expand the laryngeal aperture (only 4 of 587 patients), jaw-thrust by an assistant allowed easy passage of the ETT + stylet.

While traditional teaching has favored use of Miller blades in infants to directly lift the epiglottis, a randomized trial in children younger than 2 years intubated in the operating room setting showed that laryngoscopic views when a Miller blade was used to lift the epiglottis were not better than the view obtained when a Miller or Macintosh blade was used to lift the tongue base from within the vallecular space.18 Placing the Macintosh or Miller blade in the vallecula may also have an additional benefit of decreasing the likelihood that the laryngoscope blade is inserted too deeply, a common occurrence particularly when this procedure is performed on young infants, particularly by neonatal trainees. A case study shows that when use of a miller blade fails after multiple attempts in which only the tip of the epiglottis can be visualized, Macintosh laryngoscopy with the head in full extension aided by a 3mm ETT with a stylet appropriately curved (coinciding with the curve of the Macintosh blade) and a short handle dental mirror, was shown to be successful in a 3.9-kg infant.19

In a more recent study of neonatal intubation performed by trainees, the most common reasons for unsuccessful attempts during Miller laryngoscopy were esophageal intubation and failure to recognize the anatomy.4 In 36 (80%) of intubations, an “intubatable” view was achieved but was then either lost, not recognized or there was an apparent inability to correctly direct the endotracheal tube; therefore, intubating the esophagus about half the time. Suctioning was commonly performed but rarely improved the view. The overall first-attempt success rate and median number of attempts were 22 of 45 (49%) and 2 (2-5) (range), respectively. It can be postulated that in the cases in which there was an “intubatable” view, the reason for the apparent inability to correctly direct the ETT is because as the ETT approaches the larynx, it obscures the Cormack-Lehane grade 1 view in which there is full view of the vocal cords (see figure 2) or small opening of a Cormack-Lehane grade 2A view in which the lifted tip of the epiglottis is seen with only a partial view of the glottis exposed (see figure 3).

Figure 2

Cormack-Lehane Grade 1 view. Image used with permission, Dr Ross Hofmeyr, http://www.OpenAirway.org.

Figure 3

Cormack-Lehane Grade 2A view. Image used with permission, Dr Ross Hofmeyr, http://www.OpenAirway.org.

Because of the inexperience of neonatal trainees, they cannot easily and confidently direct the ETT into the trachea. As a result, they often intubate the esophagus.

One study of Macintosh laryngoscopy in adults compared first-attempt intubation success facilitated by a bougie versus an ETT + stylet by either emergency medicine residents (usually postgraduate year 3 or higher) or attending emergency physicians attending in the emergency room[20]. Among the 380 adult patients (18 years and older) with at least 1 difficult airway characteristic, first-attempt intubation success was higher in the bougie group (96%) than in the ETT + stylet group (82%) (absolute between-group difference, 14% [95% CI, 8% to 20%]). Among all patients, first-attempt intubation success in the bougie group (98%) was significantly higher than the ETT + stylet group (87%) (absolute difference, 11% [95% CI, 7% to 14%]).

By virtue of its smaller diameter compared with the ETT, the bougie obscures less of the operator’s full view of the vocal cords or small opening of a grade 2A view as it approaches the larynx, which allows the trachea to be intubated more easily and confidently; therefore, allowing significantly greater first-attempt success rates. The bougie also likely has a higher chance of blindly accessing the laryngeal aperture when there is a Cormack-Lehane grade 2B view in which the lifted tip of the epiglottis is seen without a partial view of the glottis (see figure 4) or when there is a Cormack-Lehane grade 3 view in which only the unlifted tip of the epiglottis is exposed (see figure 5) compared with the larger-caliber ETT.

Figure 4

Cormack-Lehane Grade 2B view. Image used with permission, Dr Ross Hofmeyr, http://www.OpenAirway.org.

Figure 5

Cormack-Lehane Grade 3A view. Image used with permission, Dr Ross Hofmeyr, http://www.OpenAirway.org.

Even during a Cormack-Lehane grade 4 view in which no identifiable structures could be seen (see figure 6), the aperture was blindly accessed with a bougie in 100% of all cases (3/3) versus in only 40% (2/5) with an ETT + stylet.

Figure 6

Cormack-Lehane Grade 4 view. Image used with permission, Dr Ross Hofmeyr, http://www.OpenAirway.org.

However, because grade 4 views are extremely rare, the eight grade 4 views were likely observed during uninterrupted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) chest compression, which prevented optimal alignment of the three airway axes, which reduced the view by one grade from a Cormack-Lehane grade 3 to a grade 4.21

Another study was conducted to assess the difficulties associated with bougie-assisted intubation in the emergency department (where residents in training perform the majority of intubations) in all adult patients (18 years of age and older) on whom all intubations were attempted with a bougie over the course of almost 2.5 years.22 Among the 25 of 88 cases where bougie-assisted intubation failed, 13 (52%; 95% CI 32.4-71.6%) reported inability to insert the bougie past the hypopharynx, six (24%; 95% CI 7.3-40.7) reported inability to pass the ETT over the bougie, four (16%; 95% CI 1.6-30.4%) reported esophageal intubation, one did not report a reason, and one appropriately did not pass the ETT because the bougie was felt to be in the esophagus (no “palpable clicks” or “hold-up”). Among the 63 first-attempt successes, 7 (11.1%) had Cormack Lehane grade 4 views, which were likely observed during uninterrupted CPR chest compression.

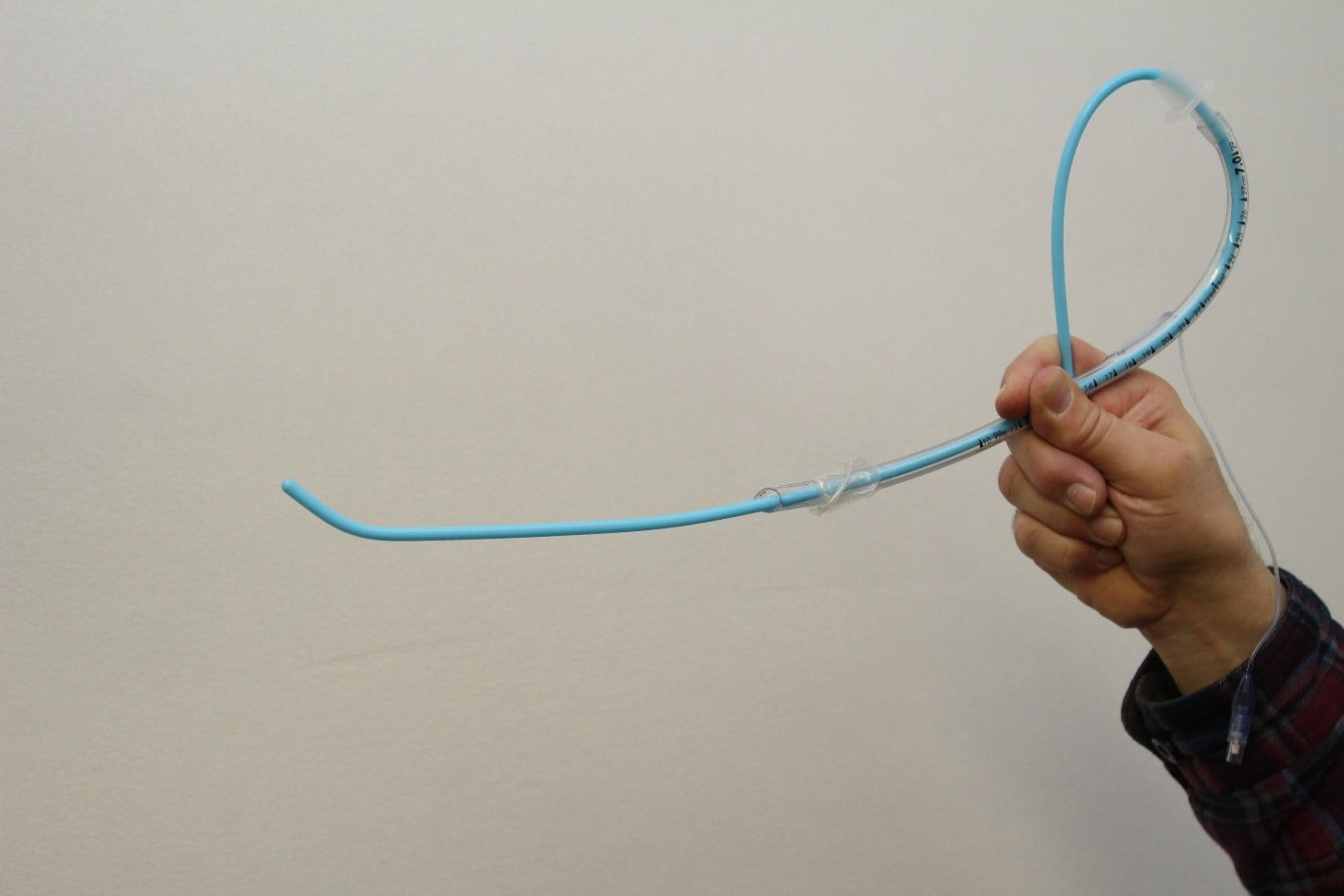

As already evidenced,16 in the 13 cases in which the inability to insert the bougie past the hypopharynx was reported, failure could have been prevented by an assistant providing jaw thrust, which fully expands a severely collapsed glottis. In the 6 cases in which the inability to pass the ETT over the bougie was reported, failure may have been prevented by using a single person bougie technique. The ETT is first preloaded onto a bougie as shown in a YouTube video of cadaveric intubation using a single-person bougie technique.23 First, the angulated tip must be adequately extended beyond the ETT bevel tip. Therefore, the bougie was first extended equally from each end of the ETT and then backed up a little so that the nonangulated end of the bougie didn’t extend too far from the tube. Because the adult trachea is 10 to 13 cm in length,24 it is reasonable to suggest that having the coudé tip extend to the 15 cm mark on the bougie would ensure that hold up can be felt if the ETT is actually inside the trachea and allows the ETT bevel tip to be only a short distance from the glottis when hold up is felt. The nonangulated tail end of the bougie is then looped forward and held against the side of the ETT with right hand, thereby allowing the intubator to perform bougie-assisted intubation without an assistant (see figure 7).

Figure 7

An adult endotracheal tube preloaded onto a coudé tip bougie for a single-person intubation technique in which the nonangulated tail end of the bougie is looped forward and held against the side of the tube with the right hand. (Image/Travis Brown)

The force exerted by looping the nonangulated tail end forward holds the angulated end against the inside wall of the ETT thereby preventing the gap between the bougie and the bevel tip. When using a bougie without preloading the ETT onto a bougie, the gap between the bougie and the inside surface of the bevel tip of a standard ETT can be substantial, which can prevent advancement of the ETT past the vocal cords despite rotating the ETT, which prevents the side bevel tip from getting hung up on the right arytenoid cartilage. Therefore, intubation bougies should be as close as possible to the size of the inside diameter of the ETT to reduce the gap and the chances of the bevel tip getting hung up on the anterior commissure of the larynx when advanced off the bougie. During laryngoscopy, the coudé tip of the bougie pointing directly upward is carefully inserted between the vocal cords, through the center of the small opening under the adequately lifted epiglottis of a Grade 2A view (or through the center area of the “crack” just below the adequately lifted epiglottis of a Grade 2B view, under the center of the tip of the unlifted epiglottis of a Grade 3A view, or through the center area of the “crack” in the middle of a Grade 4 view) and then gently advanced until hold up is felt. Once resistance is met, stop advancing immediately. With one continuous motion, the tube is then rotated counterclockwise 90 degrees, the nonangulated tail end of the bougie is then let go and the ETT is advanced off the bougie and into the trachea.

It can be postulated that jaw-thrust applied by an assistant adequately lifts the epiglottis[25], which should allow management of a bougie unliftable Cormack-Lehane grade 3b without the need to use a styletted ETT to lift the tip of the epiglottis.26 In the 5 cases in which esophageal intubation was reported, caution must be exercised when lesser experienced residents are performing bougie-assisted intubation in which the ETT is not preloaded onto the bougie.27 A properly performed hold-up maneuver would yield a negative result only if the bougie could be advanced to 45 cm without resistance thereby indicating esophageal placement.

The same benefit of bougie-assisted intubation in adults is probably achieved in children28 although reports of pediatric use are limited.29-33 Fifteen anesthesiologists performed tracheal intubation using Miller laryngoscopy and a 3mm ETT on an infant manikin at three different degrees of difficulty (normal [Cormack-Lehane grades (Cormack) 1-2], cervical stabilization [Cormack 2-3], and anteflexion [Cormack 3-4]) with or without a 5 FR (1.67 mm) tracheal introducer (or “bougie without an angled tip”).34 Cook Medical manufactures an 8 Fr/35 cm Frova intubating introducer with an angled (coudé) tip, which should be used with endotracheal tubes with an inside diameter 3 mm or larger. Five (5) Fr introducers should be used with 2.5 mm-ETTs. In the normal and cervical stabilization trials, all intubation attempts were successful regardless of whether or not the “bougie” was used. In contrast, in the anteflexion trial, only 1 of 15 participants succeeded in tracheal intubation without the “bougie” and only 8 of 15 with the “bougie”; the success rate significantly improved with the “bougie” (P = 0.005). Intubation time did not significantly change under the normal trial with or without the “bougie” (without, 12.7 ± 3.8 seconds; with, 13.4 ± 3.6 seconds).

However, intubation time was significantly shorter with the “bougie” in both the cervical stabilization and anteflexion trials (cervical stabilization: without, 24.2±10.6 seconds; with, 17.4±4.7 seconds; 𝑃 = 0.03; anteflexion: without, 59.0 ± 3.8 seconds; with, 37.2 ± 13.7 seconds; 𝑃 < 0.001). It can be postulated that use of a single person bougie technique will further shorten the intubation time because the ETT is already loaded onto the bougie. The signs, if the bougie is correctly placed in the trachea of adults and older children, of tracheal clicks when using a bougie with a coudé tip and hold-up, may not be applied to infant cases. Clicks likely cannot be felt with a straight tip “bougie” and the hold-up sign will definitely work and is safe on a manikin but there are concerns in intubation of a real infant from the viewpoint of avoiding airway trauma; therefore, a 5 Fr bougie with a coudé tip and with cm and mm markings should be developed.

Nonetheless, as already evidenced, a bougie likely has a higher chance of blindly accessing the laryngeal aperture compared with the larger-caliber ETT. Even during a grade 4 view in which no identifiable structures could be seen, the laryngeal aperture could be blindly accessed with a bougie in 100% of all cases versus 40% of ETT + stylet. When using a single-person bougie technique, since the length of the trachea in neonates is approximately 4 cm35 the bougie should extend 5 cm from the tip of the ETT (since hold up is felt when the tip of the bougie meets resistance in the right mainstem bronchus) to ensure that the hold-up sign can be felt if the bougie is actually inside the trachea and allows the ETT tip to be only a short distance from the glottis when hold up is felt. In addition, a laryngeal mirror for neonates and older infants should also be developed to guide bougie intubation when the laryngeal aperture is not visible.19,36

Without anesthesia training, intubation should not be performed using a Miller blade or a styletted endotracheal tube. When the epiglottis cannot be adequately lifted and/or the collapsed laryngeal aperture cannot be adequately expanded due to less than optimal technique or even correct technique, use of Macintosh laryngoscopy aided by a single-person bougie technique and jaw-thrust, when necessary, can overcome these difficulties and increase intubation first-attempt success rates. LifeLineARM mechanical chest compression21 or correctly performed manual chest compression37 should not be interrupted to perform intubation because use of a single- person bougie technique with jaw thrust when necessary, can overcome any difficulties.

Clinical evaluation of Macintosh laryngoscopy in infants and neonates, assisted by a single-person bougie technique using a 5Fr “straight tip bougie” (until a 5 Fr bougie with a coudé tip can be developed) and jaw-thrust from an assistant, when necessary, including complications, is needed in the future. Prehospital clinical trials comparing outcomes between use of supraglottic airways and endotracheal intubation assisted by a single-person bougie technique and jaw thrust from an assistant, when necessary, are also needed. Mirror-guided bougie intubation techniques need to be developed in the operating room prior to disseminating this technique to other healthcare professionals.

References

- Young KD, Seidel JS. Pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A collective review. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:195–205.

- Sirbaugh PE, Pepe PE, Shook JE, et al. A prospective, population-based study of the demographics, epidemiology, management, and outcome of out-of-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:174–184.

- Barber CA, Wyckoff MH. Use and efficacy of endotracheal versus intravenous epinephrine during neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the delivery room. Pediatrics 2006;118:1028–34.

- O’Shea JE, Loganathan P, Thio M, Kamlin COF, Davis PG. Analysis of unsuccessful intubations in neonates using videolaryngoscopy recordings. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103:F408-F412.

- Konrad C, Schüpfer G, Wietlisbach M, Gerber H. Learning manual skills in anesthesiology: Is there a recommended number of cases for anesthetic procedures? Anesth Analg 1998;86:635-9.

- O’Donnell CP, Kamlin CO, Davis PG, et al. Endotracheal intubation attempts during neonatal resuscitation: success rates, duration, and adverse effects. Pediatrics 2006;117:e16-e21.

- Downes KJ, Narendran V, Meinzen-Derr J, et al. The lost art of intubation: assessing opportunities for residents to perform neonatal intubation. J Perinatol 2012;32:927–32.

- Leone TA, Rich W, Finer NN. Neonatal intubation: success of pediatric trainees. J Pediatr 2005;146:638-41.

- Haubner LY, Barry JS, Johnston LC, et al. Neonatal intubation performance: room for improvement in tertiary neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation 2013;84:1359-64.

- Bismilla Z, Finan E, McNamara PJ, et al. Failure of pediatric and neonatal trainees to meet Canadian neonatal resuscitation program standards for neonatal intubation. J Perinatol 2010;30:182-7.

- Kamlin CO, O’Connell LA, Morley CJ, et al. A randomized trial of stylets for intubating newborn infants. Pediatrics 2013;131:e198-e205.

- Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, et al. Proficiency of pediatric residents in performing neonatal endotracheal intubation. Pediatrics 2003;112:1242-7.

- Le CN, Garey DM, Leone TA, et al. Impact of premedication on neonatal intubations by pediatric and neonatal trainees. J Perinatol 2014;34:458-60.

- Hatch LD, Grubb PH, Lea AS, et al. Endotracheal intubation in neonates: a prospective study of adverse safety events in 162 infants. J Pediatr 2016;168:62-6.

- Wang HE, Kupas DF, Hostler D, Cooney R, Yealy DM, Lave JR. Procedural experience with out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1718-1721.

- Takenaka I, Aoyama K, Kadoya T, Sata T, Shigematsu A. Fibreoptic assessment of laryngeal aperture in patients with difficult laryngoscopy. Can J Anaesth 1999;46:226-31.

- Murashima K, Fukutome T. Effect of jaw-thrust manoeuvre on the laryngeal inlet. Anaesthesia 1998;53:203-4.

- Passi Y, Sathyamoorthy M, Lerman J, et al. Comparison of the laryngoscopy views with the size 1 Miller and Macintosh laryngoscope blades lifting the epiglottis or the base of the tongue in infants and children <2 yr of age. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:869-74.

- Patil VU, Sopchak AM, Thomas PS. Use of a dental mirror as an aid to tracheal intubation in an infant. Anesthesiology 1993;78:619-20.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, et al. Effect of Use of a Bougie vs Endotracheal Tube and Stylet on First-Attempt Intubation Success Among Patients With Difficult Airways Undergoing Emergency Intubation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;319:2179-89.

- Truszewski Z, Czyzewski L, Smereka J, et al. Ability of paramedics to perform endotracheal intubation during continuous chest compressions: a randomized cadaver study comparing Pentax AWS and Macintosh laryngoscopes. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:1835-9.

- Shah KH, Kwong B, Hazan A, Batista R, Newman DH, Wiener D. Difficulties with gum elastic bougie intubation in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med 2011;41:429-34.

- Kevin High from Vanderbilt University Take 5: 5 airway bougie tips https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrHZAPLPKwU [accessed on 16.12.10].

- Brand-Saberi BEM, Schäfer T. Trachea: anatomy and physiology. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:1-5.

- Durga VK, Millns JP, Smith JE. Manoeuvres used to clear the airway during fibreoptic intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:207-11.

- Hung TY, Lin CH, Lin LW, et al. Lifting of epiglottis superior to preloaded bougie technique when only the epiglottis is visible: a randomized, cross-over simulated mannequin study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020;27:147-148.

- Weingart SD. Bougie placement and the hold-up sign. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:1152.

- King BR, Hagberg CA. Management of the difficult airway. In: Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine Procedures, 2nd ed, King C, Henretig FM (Eds), Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2008. p.191.

- Semjen F, Bordes M, Cros AM. Intubation of infants with Pierre Robin syndrome: the use of the paraglossal approach combined with a gum-elastic bougie in six consecutive cases. Anaesthesia 2008;63:147.

- Arora MK, Karamchandani K, Trikha A. Use of a gum elastic bougie to facilitate blind nasotracheal intubation in children: a series of three cases. Anaesthesia 2006;61:291.

- Teoh CY, Lim FS. The Proseal laryngeal mask airway in children: a comparison between two insertion techniques. Paediatr Anaesth 2008;18:119.

- Picard N, Lakhnati P, Guillerm AL, Sebbah JL, Dhonneur G. [High-risk airway management in pediatric prehospital emergency medicine]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2010;29:308.

- Camkiran A, Pirat A, Akovali NV, Arslan G. Combination of laryngeal mask airway and pediatric Boussignac bougie for difficult tracheal intubation in a newborn with Goldenhar syndrome. Anesth Analg 2012;115:737.

- Komasawa N, Hyoda A, Matsunami S, Majima N, Minami T. Utility of a gum-elastic bougie for difficult airway management in infants: a simulation-based crossover analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:617805.

- Wheeler, D., Spaeth, J., Mehta, R., Hariprakash, S., Cox, P., 2009. Assessment and Management of the Pediatric Airway. In: Wheeler, D.S., Wong, H.R., Shanley, T.P.(Eds.), Resuscitation and Stabilization of the Critically Ill Child SE-4. Springer,London, 1–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84800-919-6_4.

- Weisenberg M, Warters RD, Medalion B, Szmuk P, Roth Y, Ezri T. Endotracheal intubation with a gum-elastic bougie in unanticipated difficult direct laryngoscopy: comparison of a blind technique versus indirect laryngoscopy with a laryngeal mirror. Anesth Analg 2002;9532:1090-3.

- Rottenberg EM. A simple method of performing maximally effective CPR chest compressions. Resuscitation. 2019;138:213-214.

Eric M. Rottenberg, AAS, is a graduate of the Columbus Technical Institute with a paramedic degree. He has worked at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center since 1988, where he has studied CPR and intubation research. He has spent several years reviewing manuscripts for the American Journal of Emergency Medicine and received reviewer recognition in 2019 after completing his 80th review.

Recent Comments